Chasing the Crescent Moon of Safar 1447 – July 2025:

When I set out to observe the crescent moon of 25 July 2025, I was filled with both confidence and anxiety. Confidence, because with a clear sky, I was sure I could see it. Anxiety, because the moon would be just +5.48° above the horizon at sunset, leaving little margin for error for such a thin crescent moon.

The Journey Begins – 23 July 2025:

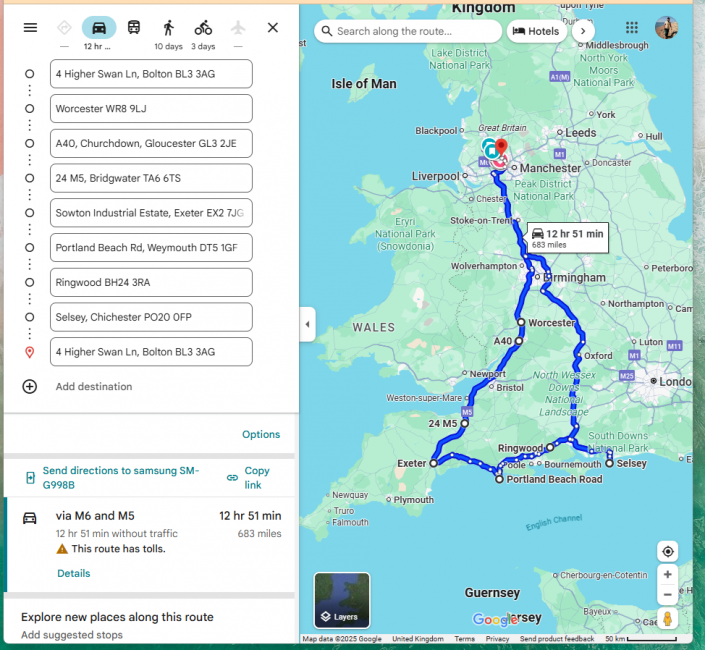

I left home at around 17:00 for Coverack, Cornwall, aiming to observe the waning moon on the morning of 24 July 2025. The weather forecast was uncertain, but since I was keen to record data for myself, I decided to take the chance. Along the way, I stopped frequently for prayers and food, while also monitoring the forecasts. It was an overnight drive in darkness—tiring, but my objective kept me excited.

24 July 2025 – The waning moon:

By the time I reached Exeter, I had decided that Coverack was not worth the effort, and instead, I turned east, eventually arriving in Weymouth. By then, it was already 24 July. The spot seemed ideal: reasonably clear skies, although not entirely cloud-free. Unfortunately, the haze was so dense that even the rising sun appeared very dim. I tried my best, but I couldn’t see the moon at all. The section of the sky where the moon was expected to appear remained extremely dense.

After packing up, I slept in my car on the beach. The weather was hot, so I slept comfortably for about four hours before noise woke me. I chose to stay at the same location for the waxing moon observation on 25 July, since forecasts predicted cloudy skies further north but clearer conditions where I was. I freshened up at a nearby Tesco and spent the day mostly in my car, reading the skies, trying to find warm food, and exploring nearby areas. Later, I went up Yeates Road in Portland to observe the sunset, but once again the lower sky was very dense, though the solar disk was still visible.

That evening, I focused on my next priority: the waxing crescent on 25 July. While forecasts were promising, the horizon was my primary concern. There was nothing more I could do, so I decided to stop worrying, pray, have a snack, and rest again in my car.

Daytime Imaging – A Breakthrough – 25 July 2025

I woke up refreshed and still excited for the waxing crescent, even though I had missed the waning moon on the 24th. After freshening up, I set up for daytime imaging. Initially, I faced problems because the latest software update had broken my old processing script, which took over an hour to fix. Alhamdulillah, once fixed, I managed to capture my lowest-ever elongated moon in broad daylight—a small but significant achievement.

Afterwards, I debated where to go for evening observations. Forecasts looked very good in Scotland, but I was too far, too tired to drive, and worried that conditions there might still fail near the horizon. In the end, I stayed where I was—a decision I later thanked Allah for, since later Scotland’s skies turned out cloudy despite forecasts.

Still, the local skies in Weymouth below 4–7° altitude were troubling. By mid-afternoon, calculations convinced me to move again. I decided to leave Portland after spending two nights there and head toward Selsey, hoping to dodge the clouds. It was a long and tense three-hour journey in traffic, and over the 160km, the lower sky remained cloudy, but my instinct told me that Selsey would offer a better chance.

Arrival in Selsey – 25 July Evening

I arrived at a beach car park around 18:35 and quickly scanned for a setup location. Unfortunately, the moon’s alignment at sunset meant I had to set up along a public walking path, which could cause issues if people stopped, as it might obscure my view, or some might ask me to move, meaning no observation. Despite the challenges and the time setting in, I took a calculated risk and managed to complete my setup, with my astro camera already able to detect the moon.

While waiting for sunset, I texted a Muslim brother nearby to join me as a witness, but he was out of town. I then approached a lady on the beach with her son, who had been watching me set up. I explained the importance of having a witness and asked her to return at sunset, which she kindly promised to do. Many other passersby admired my setup, but most could not commit to staying until sunset.

The Final Show – Observation of the Crescent

I began observing just a few minutes before sunset, I kept trying through my telescope, though I knew it was unlikely to be visible yet. The clouds had cleared by now, but the lower horizon was still very dense. I was tense—the clock was ticking. Through my telescope, I could see Mars, but not the moon.

Then, suddenly, after minutes of straining, the crescent became distinguishable. I screamed so loudly that everyone around stared at me: “Yes! I can see it!” The time was 21:13:xx.

The lady I had spoken to earlier, Ingrid, had indeed come back and was waiting nearby with her son. But since I had gone silent after sunset, she stood a little distance away, unsure. I waved and called to her urgently: “Please run, please run and have a look if you can see it!”

Before letting her view, I checked again. The crescent was barely there, but visible—that was my second sighting. Ingrid then leaned over to the eyepiece. For 20–30 long seconds, she searched carefully, and then her voice lifted: “Yes, I can see it!” I immediately asked her to describe what she saw and the location in the sky—and her description was perfect.

Encouraged, I looked again myself. This time the crescent appeared straight away—my third sighting. I then invited Ingrid once more, and she confirmed it again. Her young son wanted to try, but I gently apologised, explaining that we didn’t have time to train his eye on such a subtle crescent. His mother explained to him that he would have another chance one day.

When I first cried out that I had seen the crescent, a man named Callum Birch-McGowan, visiting Selsey from Guildford, had come over to stand beside me. I invited him to try the telescope. Before handing it over, I looked again myself—the crescent was still there. I then gave Callum around 30 seconds or more at the eyepiece, but he was unable to detect it.

I asked him to step aside, looked again, and confirmed my fifth sighting<, though by now the moon was sinking into the denser layers of atmosphere and becoming harder to hold. I let Callum try once more, but again he said he could not see it. Finally, I returned to the eyepiece for a sixth and last sighting, and this time I watched the crescent fade and vanish completely into the dark haze of the horizon. I immediately glanced at my laptop clock to note the time: 21:19:xx.

Photographing the crescent with a DSLR:

Up until then, I had not attempted to take a picture with my DSLR camera without the telescope attached, as I was busy into bringing in witnesses and guiding inexperienced observers. From the outset of this journey, however, I was clear that my ultimate aim was to capture the crescent with my DSLR.

As I have explained in earlier reports, achieving everything single-handedly in just a few minutes is never simple. So, I asked the others to step aside to allow me to take pictures. I then moved my DSLR with a tripod, roughly aligning it with the telescope, and began taking a series of carefully judged shots. At that moment, I could not be certain whether the camera was pointed precisely in the right section of sky, nor whether the moon—if in frame—would even show through the increasingly dense atmosphere.

By around 21:25, looking through the eyepiece, I could see only a wall of dark haze where the moon had been. Even the astro-camera is no longer able to capture the crescent moon. At that point, I knew the crescent had gone and I ended the observation and took pictures.

It is worth noting that during the first six minutes of visual sightings and the subsequent six minutes spent with the DSLR, I did not attempt any naked-eye observations, due to a lack of time. In practice, this means I would report a negative naked-eye sighting as I did not have the opportunity to try.

After the Observations and Journey Home:

After the observation, I was filled with joy. The four of us chatted for a while, and they expressed how impressed they were with the effort and organisation that had gone into achieving just six minutes of crescent sightings. Callum Birch-McGowan, in particular, admired my passion, repeating several times how rare it is these days to see such a commitment to something one truly loves. Although he could not see the moon himself, I reassured him: this was an exceptionally difficult crescent, sitting very low, and it sank quickly into the dense atmosphere. He did not have enough time to work it out through the eyepiece—but there will be other opportunities.

We took some photos together, exchanged details, and then I let them go. I stayed behind, taking in the quiet beauty of the sky. I felt deeply content at having achieved the objective: sighting such a thin and low crescent.

Packing up took about an hour. During that time, I filed my observation report. Before leaving, I quickly checked my DSLR images, but to my disappointment, I could not see the moon in them. I prayed Maghrib and Isha together, then began the long drive home.

On the way, I stopped for a rest at a service station. In that calmer environment, I reviewed the DSLR shots again—and this time, Alhamdulillah, the crescent was visible in many images. I felt a wave of relief and whispered softly, “Alhamdulillah.”

I had begun those DSLR exposures only after the crescent had stopped seeing visually from the eyepiece. It is possible that, in those six minutes, had someone else continued observing visually, the moon might still have been seen. Or perhaps it had already vanished to the eye but remained detectable on camera, recoverable later through post-processing. Either way, I was grateful—the DSLR had captured what my eye no longer could.

Reflection

In total, I spent three nights on the road, covering about 1,100 km for this moon chase. At my location, the moon’s altitude at sunset was +5.48°. I first observed it at +3.31° and last saw it at +2.46°, giving me a viewing window of just +0.85°. Without precise calculations, I would not have seen it at all.

If the sky had been clear below +2.46°, I could have observed it longer and shared the sight with more people. Still, I am grateful—I saw it for six minutes, captured it with my DSLR, and witnessed the joy of others around me.

This was an unforgettable journey—one of persistence, planning, and patience.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!